Ben Brewster is a professional pitcher, founder of TreadAthletics Online coaching and author of "Building the 95 MPH Body".

Ben Brewster is a professional pitcher, founder of TreadAthletics Online coaching and author of "Building the 95 MPH Body".

Inside Pitch: What’s your background in baseball and how you developed your passion for teaching?

Ben Brewster: Contrary to most players who end up playing professionally, I wasn’t the star player growing up. I was just an athletic, skinny kid who had no idea how to swing or throw properly and never had any formalized instruction. Entering high school, I was 6’3” and weighed 150 lbs. I threw about 70 mph. I really got hit around when I faced high school hitters for the first time, which exposed my lack of ability and preparation. It was a defining moment in my career.

I ended up pouring myself into learning everything I possibly could, spending hours a day reading online forums, pitching books, strength and conditioning manuals, nutrition articles – anything I could get my hands on. I made it my mission to play Division I baseball and throw 95 miles per hour.

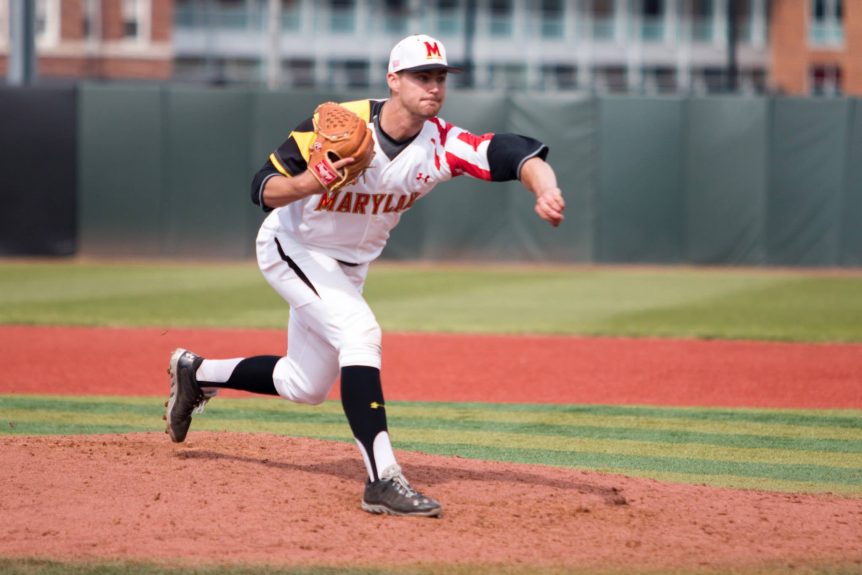

Towards the end of my high school career, I was throwing in the mid-80s, but I had zero college offers. I decided to go to University of Maryland to study exercise science, which I was hoping would help with my baseball aspirations.

The plan was to keep training and try to walk on to the team each year until I made it. I made the team, but basically rode the bench until my senior year, when I played a role in helping that team get within one win of the College World Series.

I topped out at 95 that year and was drafted by the Chicago White Sox in the 15th round. After a couple years and an elbow surgery, I got up to sitting 96-98 miles per hour in bullpens and am still actively chasing a return to pro baseball as a 27-year-old. The plan is to keep training and try to make my MLB dream a reality each year until I make it!

I began coaching in 2015 during my first year as a pro pitcher. People were reading my blog and began reaching out. It has grown into something more than I could have ever imagined, with us now being a five-person company and having coached 600+ athletes through remote training. We have also had 27 remote athletes drafted since 2017 and consult with high school travel organizations college programs. Word has finally begun to get out that remote coaching can and does work for highly motivated athletes and with the right system. We’re incredibly excited to be opening our first facility and begin to offer an in-person coaching component as well in 2020.

IP: What are the methods you use to implement new training/concepts with your clients?

BB: We’re constantly searching and striving for optimization and individualization. How can we make each mobility drill, throwing program or exercise better or adjust it based on an athlete’s specific limitations? To me, coaches that pigeon-hole themselves in one philosophy are massively missing the boat. I’m not a “weighted ball guy” or a “long toss guy” or a “pitch-design guy” – I’m a “results guy.” Specific drills and exercises are only as good as their application. These are all tools in the toolbox, so to speak, that must be used and applied in the right context.

This is where having a thorough movement assessment and understanding of each player’s biomechanics and body limitations becomes so crucial. The slow-twitch, 15 year-old pitcher who can’t do 10 bodyweight push-ups and has never even had a sore arm needs to be trained completely differently from the 23 year-old fast-twitch pro who is dealing with chronic arm injuries but already has a massive strength base. The drills and exercises we prescribe must change.

Throwing mechanics still have so much uncharted territory associated with them that much of what we do is problem solving issues for higher level players. Anyone can get a guy from 70 to 80 miles per hour. That’s easy. What’s not easy is getting the 92-mile per hour guy to 96. That’s where you begin working through everything with a fine-toothed comb for each guy to squeeze as many variables out of that metaphorical tube of toothpaste as possible.

IP: How should pitchers balance mechanical/delivery work with competition/performance?

BB: The real time to make mechanical changes is in the off-season. You simply have to take advantage of that time to deconstruct the mechanical issue without having the player worrying about the dozen other variables that come into play when throwing in a game. Then you begin introducing more variables and challenging the new pattern as it begins to stick. Let’s say an athlete is focused on improving velocity using long toss. To get that pattern to transfer, we need to be able to bring that back down to a pitching-specific release point (one variable) within a delivery (another variable) to a target 60 feet away (another variable), then add in the mound as another variable, then introduce stand-in hitters, off-speed, etc. Patterns don’t usually transfer well when you introduce 15 new variables and then blame the kid for not having pinpoint command or even worse, call him “mentally weak.” That’s just bad coaching.

In-season, having one or two mechanical “anchors” to work on in pre-throwing drill work each day is probably fine, but the focus must be kept on competition. The last thing you need when the game starts is to be worrying about where your glove arm is or where your wrist is at ball release. That’s the time to go out there and compete.

IP: What are a couple things young players can do to improve their mechanics quickly?

BB: Be an athlete, not a robot.The way many old school pitching coaches work on mechanics ingrains slow, robotic movements that become much harder to break later on and totally rob kids of the smoothness and athleticism that is required to throw at a high level.

IP: Mechanically speaking, what is the most overrated “old school” pitching advice? And conversely, what’s one that’s stood the test of time?

BB: I would say the most overrated is ‘finish over your front side.’ What people don’t understand is that the throw is a finely sequenced loading and unloading event and by the end of the throw you have very little control over the positions and postures you’re in, because it’s an unloading or a result of the positions and postures you established in the start of the throw. Just trying to “finish over your front side” ruins the flow of energy, and people are starting to realize that with the entire backlash against old school drills like the towel drill, or with coaches that now have immediate Rapsodo or radar feedback and see the immediate detrimental effect of such advice.

Cues like that are individual specific anyway, so how one athlete’s body interprets a cue like “finish over your front side” or is going to be different than another. Take “stay back,” for example. I think that’s a good option for an athlete who has a tendency to leak forward and let the arm action come into the throw too early. I also like the cue of “find the heel” for encouraging athletes to shift their weight properly by utilizing the rear glute and lateral hip musculature versus jumping or lunging towards the target with their quad. But don’t get me started on “balance points,” “drop and drive” or “tall and fall”!

Many athletes are dealing with structural limits that prevent them from getting in and out of many of the positions coaches harp on. Flying open or not finishing properly or not getting downhill are all things that have a high structural demand. If an athlete doesn’t have good front side hip internal rotation, or glove side thoracic rotation, or the hamstring on his lead leg is tight, or he has a history of ankle instability or previous injury, all of these potential factors come into play. Understanding things from the skill side, but also the biomechanical and anatomical side as well is where the real next level results lie, because there is so much interdependency of these things.

Getting stronger is one of the quickest ways to improve mechanics and athleticism. Even if a kid is 12 years old, he can still be working on bodyweight movements – pushups, squats, lunges and bodyweight rows, to teach him how to coordinate and use his body better.

IP: Coaches all go through trial and error with their teachings and methods. What is one example where you’ve changed or adapted your earlier teachings to adjust to new information you discovered?

BB: One misconception that a lot of players and coaches have, and that I had early on, is thinking that the training methods that get a player from a beginner to an intermediate level is what’s going to get them from an intermediate to an advanced level. Case in point: strength.

Getting an athlete from a 135lb to a 315lb back squat is going to have unbelievable benefit to his performance and overall power output. Do that across the board and you’ve got an entirely different athlete on the field. The problem comes when we then assume that continuing to push strength numbers even further up will continue to have the same effects. When it comes to baseball (and any power sport), there is a pretty unforgiving point of diminishing returns. I see so many athletes with good work ethics that trained themselves from 78 to 88 mph and they think that just getting even bigger and even stronger is going to get them to 92 mph. It just doesn’t work that way once a strength base is built. Power specific training, movement efficiency, mechanics, soft tissue quality, recovery, and all of these other variables take precedent over strength for the more advanced athletes.