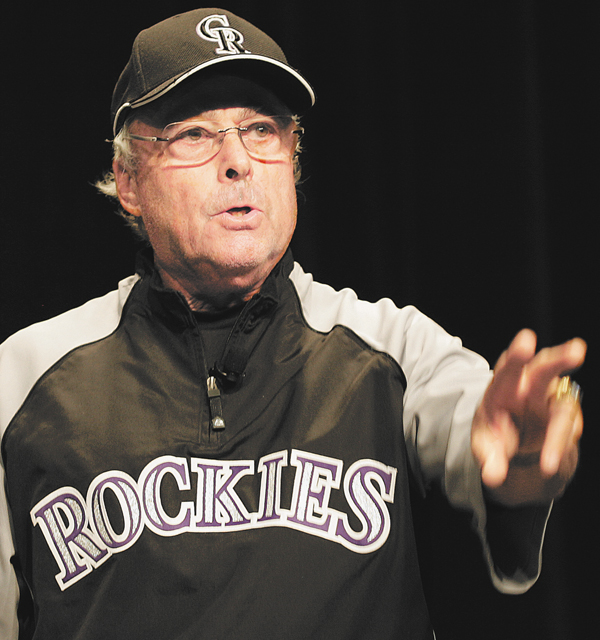

Jerry Weinstein is a graduate of UCLA where he played for ABCA Hall of Fame coach Art Reichle. As a coach, Weinstein spent 23 years at Sacramento City College, compiling a record of 831-208 with a National Championship in 1998. Sac City was voted the Community College program for the decade of the 90’s by Collegiate Baseball Newspaper. During his tenure, the Panthers produced 28 Major League players and had 213 players drafted.

Jerry Weinstein is a graduate of UCLA where he played for ABCA Hall of Fame coach Art Reichle. As a coach, Weinstein spent 23 years at Sacramento City College, compiling a record of 831-208 with a National Championship in 1998. Sac City was voted the Community College program for the decade of the 90’s by Collegiate Baseball Newspaper. During his tenure, the Panthers produced 28 Major League players and had 213 players drafted.

Weinstein has been active in International baseball with Team USA (1970 University Games, 1989 Pan Am Games, 1992 Olympic Team, 1996 Olympic Team) and with Team Israel (2017 World Baseball Classic). He has also served in professional baseball as a minor league manager for the Montreal Expos, Chicago Cubs and Colorado Rockies, and has held posts as the catching coordinator for the Milwaukee Brewers, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and the Rockies, with whom he is still employed.

Jerry is a member of the California Community College Baseball Hall of Fame, the Sacramento City College Athletic Hall of Fame, the ABCA Hall of Fame and the La Salle Club Coaches Hall of Fame.

Inside Pitch: What have been your takeaways from your stops along the coaching road?

Jerry Weinstein: It’s funny, I feel sorry for those guys I coached when I was in my twenties. I thought I knew everything and I knew nothing. Even today, the more you know the less you know. Certainly as you mature, I think it becomes more about the players and less about you as a coach; more about relationships and less about your resume.

As you mature as a coach, the player becomes more important and the scoreboard is less important. The process becomes more of the focal point and the outcome is less important. If you have a good process and you have the right players, chances are you are going to have a good outcome.

IP: What are your personal goals with coaching now versus what they used to be?

JW: I don’t really have any specific goals. I don’t have a bucket list that I want to do or need to do. I just try to put myself in an improvement mindset on a daily basis. I haven’t even thought about how long I’m going to coach. I love working for the Rockies, I have a pretty diverse job right now and it gives me a chance to do some things that I normally wouldn’t have the opportunity to do. I get a chance to manage in the Cape and do some scouting, I look at all of the top amateur catchers for our scouting director, I get to participate in spring training and instructs.

IP: How have you become such a good teacher of coaches?

JW: I have just made it a priority. You get a bit older and you have a passion for the game and you want to try to make it better. I go to clinics to share information, but also to get information. I just don’t go to the clinic to speak and then go back to my room. I always listen to all of the clinicians that are speaking. I always start off all of my talks with a buffet table analogy. I don’t have all the answers and if you can find one or two things, then great. You don’t eat all of the food at the buffett, and some guys say ‘I am not trying any of the green stuff,’ that’s fine, no problem.

What I put out there is just a bunch of suggestions based on experiences that I have had. I am not saying that I’m right or wrong, but I care for the game so I just throw stuff out there. I don’t profess to be an expert, I’m sure there are experts out there, but I am not one of them. I do have information and I share it and I have never been really concerned or secretive about it.

Some coaches employ new ideas systematically and consistently, others treat them like it’s a new toy on Christmas day – they’ll do it for a couple of days, or a couple weeks, or a couple months and then they go onto a new toy. The key is to keep it simple and repeat it and especially adapt to the individual differences of the players.

IP: Speaking of keeping it simple, are there any particular drills that have just withstood the test of time for you, that you see yourself going back to over and over again?

JW: For me, the most important thing in any drill is specificity. It’s the key to anything that we do in training for this game and unfortunately, that’s probably one of the weaknesses in our game. We don’t train specifically enough, we don’t train at game speed or above, we don’t train at game complexity or above. Are we taking ground balls making every play in 5.5 seconds or 4.1 seconds? Are we throwing BP at 60mph and swinging every three seconds? Is BP an aerobic activity or do you get the chance to reset like you’re in a game? It’s more about quality than quantity, and I think quality has suffered as a result of too many reps.

Ultimately, you’re trying to teach your players to learn how to organize their bodies to achieve a particular goal. If I’m trying to hit the ball out of the ballpark, I’m going to swing harder and try and hit a different part of the ball than I am if I’m just trying to hit a low hard-ground ball or line drive. If I want to throw the ball hard, I need intent to throw the ball hard.

The less verbiage relative to mechanics, the better. Putting a guy in a drill environment that forces them to do certain things mechanically that will produce the best external result is ideal. That way, the player has a chance to learn how to organize his body. Over time and repetition, you can build up a conditioned response to that movement pattern that will produce the best results.

The best lessons are self-taught. We all want players who can make adjustments on their own. I tell coaches the same thing- your job is to eliminate your job. If we can teach players how to figure things out for themselves, that certainly is going to be the best and most long-lasting lesson.

IP: Describe the commitment that you’ve made personally to the technological advances in player development.

JW: The old-timers may tell you that they don’t need a radar gun to know that the guy’s got a good fastball or a stopwatch to identify a good runner. I’m not saying that all this technology isn’t an improvement- it is. Because as a pitcher, for instance, I’m trying to achieve velocity and get feedback on every pitch that I throw, and I know that if I’m working on intent or direction – then I can make the adjustments that I need to make and figure out exactly what I need to do to accomplish whatever goal I have.

I try to find stuff every day – and I’ve been doing this for a long time – I’m 75 now, and I’m still looking for better ways to help athletes maximize their physical abilities. I think that it behooves coaches to utilize every tool that we can, and if we can quantify things so that players can ‘see it’ rather than ‘hear it,’ you know they can really tell the difference between a particular technique and what effect it has on their performance.

Fred Corral introduced me to the Pocket Radar, and I’ve used it a lot when I’m evaluating raw arm strength with position players, and with pitchers in flat ground and bullpens for speed differentials. It’s a handy tool, I have a number of them that I’ll hand out to players. When you couple that with their new Smart Coach, you’re able to get immediate feedback, which is especially helpful during batting practice.

IP: What are your general thoughts on developing hitters?

JW: The goal is to hit the ball hard. You can talk about launch angle and ball flight and all that, but ultimately the balls that get hit the hardest are the ones that have the most successful results. I’ll set up the Smart Coach behind the cage so players can associate a particular ball flight with their highest exit speeds.

Sometimes hitters can’t time pitches because they’re so tied up in the mechanics of hitting, which detracts from our ability to redirect the eyes and react. So by just letting your body organize itself and then getting the immediate feedback with the Smart Coach, knowledge of results immediately is really powerful for me. With your eyes you see, but you really don’t quantify like the radar gun does, whether you use it as an exit speed tool, a hard-hit tool, a pitch differential tool or assessing the overall health and wellness of a player.

I don’t think the mechanics of hitting have changed. The critical point is at the point of contact, and when you look at Babe Ruth, the point of contact is palm up, palm down, back leg is kind of L-ish, the front leg is firm, head and eyes are at the point of contact, the point of contact is at or close to 90 degrees. You look at today’s players at the point of contact and other critical points and they’re pretty much the same.

We have different terminology now. We’re talking about launch angles and exit speeds, but hitters have always wanted to hit line drives. Growing up, I knew a guy named Kenny Myers, who was a scout for the Dodgers. I remember him saying to me ‘hey Weinstein, there are no extra-base hits on the ground.’ He was talking about getting the ball in the air 60 years ago.

Then certainly, I think technology is really impacting the game in terms of pitch selection and pitch location. Back in the day if you threw a ball up and it got hit, nineteen guys were telling you to get the ball down. That is not happening now.

IP: So how do you digest that type of information and then when it comes to developing players?

JW: It’s a trial and error thing. You heighten the awareness and then it’s their choice whether they are going to test the waters, and most of them will. There is no secret information out there now, but the game has changed- the way that it was done then is not necessarily what is effective today. For example, there’s a very high percentage of breaking balls and elevated fastballs at the MLB level.

That’s not to say that the current style wouldn’t have worked as well or better back in the day. In fact, it probably would have, because it’s working right now. But the strikeout seems to be more acceptable to hitters than it was; everybody’s got their driver out and it’s a long drive contest on every pitch, whereas hitters used to throttle it down, reach for a seven iron and put the ball in play.

There are a lot of variables that factor in, but I think that one of the biggest problems right now is the dichotomy between the analytics guys and the on-the-field guys. I was just talking to Curtis Conley, who wrote Game Changer. He writes about CSI Technique- start with the evidence and work your way back. The evidence is on the field, so you have to start with the on-the-field people. If they think a guy doesn’t have good bat speed and can’t drive the ball as a result, for example, you work your way up the chain to the biomechanics and the analytics guys.

Then you can test the player’s mobility, rotational force and rotational speed. Maybe it’s a physical constraint relative to strength, maybe it’s a physical constraint relative to relative to flexibility or mobility. Or maybe it’s just an intent thing; there are a lot of young pitchers who revert back to what they were told as a youngster when it was ‘hey Johnny, nice and easy, just hit your target.’ As a result, Johnny has nice easy slow delivery and slow arm speed and when he gets to high school he can’t make the freshman team because he is throwing 69 mph. In reality, there may be a lot more left in the tank. Everything is about finding that sweet spot with players. There is no ‘always’ or ‘never,’ you just have to find out what works.