Mental Aspects of Anticipation: Analysis of Research Findings

Motor Learning experts and baseball coaches universally agree that anticipation is a key cognitive skill that is necessary to master in executing baseball skills, including ball-in-the-dirt stealing or scoring. Anticipation applied to executing various baseball skills has not been precisely defined. However, from the extant literature, we can define baseball anticipation as:

A reasonably accurate prediction of an upcoming outcome(s) based on an accumulation of information prior to the actual event.

The Central Nervous System (CNS) and Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) mechanisms are not well understood in the context of the anticipatory mechanism related to sport skill execution. Better understood and studied are the anticipatory factors that are associated with highest level of competition in a variety of sports. Highly-rated athletes across a variety of sports don’t hurry when applying anticipation and outperform mediocre players when anticipation is instrumental in successfully succeeding at a specific skill.

Techniques: Primary and Secondary Leads and Break Techniques

Technically, the primary lead begins with runner’s left heel at the corner of a base facing the pitcher’s mound at all bases. The goal is to obtain a maximum primary lead to minimize the number of steps needed or time before launching into a slide at the next base or home. Application of knowledge attained from observation of opponents, video-tape drills and daily live practice and game situations is necessary for continual improvement.

The right foot step and left foot slide technique ensures both feet are on or close to the ground if a pitcher attempts a pick off at each base during the primary lead. In that case, it’s a right foot plant, left foot pivot, dive elongating the body, and reaching with the right arm away from fielder’s glove. The length of the primary lead depends on runner’s reaction time diving back to each base and the pitcher’s quickness to each base or home.

The knees, upper body, and elbows are bent at 45 degrees with clenched fists in front of the letters. A haphazard or lower body position as commonly seen in 98% of the players today (arms hanging in front of body and upper half of body bent at 90 degrees) requires the first body move to be up and increases the steps to or time to launching the slide.

The straight steal break technique during a primary or secondary lead is to reach with the right foot (distance depends on one’s height), drive the right elbow toward the right side or ribs, punch across the letters with the left arm about 12” higher than right arm, and stride as long as possible with left leg. The goal is to be in full stride as quickly as possible.

Note: Other running experts including baseball coaches may have taught and their players have mastered a different break technique. The “proof of the pudding” is the fastest time needed react to a pickoff move and to attain a full running position in the quickest possible time. Implement any technique that players have mastered and allow them to share it with teammates. The secondary lead begins with a read of a pitcher’s move to home with the same body position as the primary lead and involves three controlled shuffle steps with the shoulders square or facing the infield grass. The combined length of the primary and secondary lead is theoretically 18 feet. Adjust the length based on live practice against pitchers at every base as the lead lengths will vary depending on a number of mental and technical factors. Repeated primary and secondary lead live practice against pitchers drilling to improve holding runners or pickoffs at each base needs to be regularly incorporated in practice, scrimmages, and off-season drills.

The goal of aggressive leads and base stealing is to force all defensive players to execute faster mentally and physically employing strategies favorable to the offense (i.e. calling less off-speed pitches, pitchers devoting unnatural attention to runners, or infielders playing closer to second or third base).

Developing Reads and Implementation of Anticipation

During the secondary lead, the runner at any base needs to focus on the ball when it breaks from the glove and follows it to a point after the release and then picks up the ball at 10 feet in front of the contact point location. If contacted, the ball’s angle will be down (ground ball), out (line drive) or up (ball in air). This and the following processes develop and implement anticipation and must be regularly practiced. A video-taped slow-framed release will show [1] the beginning and end points of all hand positions for the each pitch, [2] the ball’s trajectory after it’s released, and [3] at what distance from the release point the ball will contact the ground?

Players must continually view the video until they have mastered each hand action just before the release point and the ball’s trajectory. Two questions need to be addressed: [1] which hand position(s) for each pitch will cause the ball’ trajectory to be down or in the dirt and [2] when does a runner break during the secondary lead (first, second, or third step)? The goal is for runners to break when the ball’s trajectory is down, forcing catchers to cleanly scoop and throw to second or third or efficiently block balls with runners on third.

Players at the higher levels may employ different anticipation methods because of expert coaching at lower levels. Brian Roberts, son of ABCA Hall of Famer Mike Roberts, attained consistently high percentage success in stealing second and third during his career. Besides collecting data on opponents and implementing various lead and steal techniques taught by his father, Roberts’ main weapon was to utilize a jump start when leading at first or second.

At a certain distance during the primary lead at first, the pitcher is unable to see the runner regardless of how far the head is turned. At this distance, if the runner reads home and is still moving, this triggers either a break to or a dive back to the base. At second, the runner can attain a longer primary lead and if moving and reads home, break and steal. (between 2005-2009, Roberts’ third base stealing success was a stellar 92% (60 out of 65).

Scoring on Balls In The Dirt or Misplayed Pitches

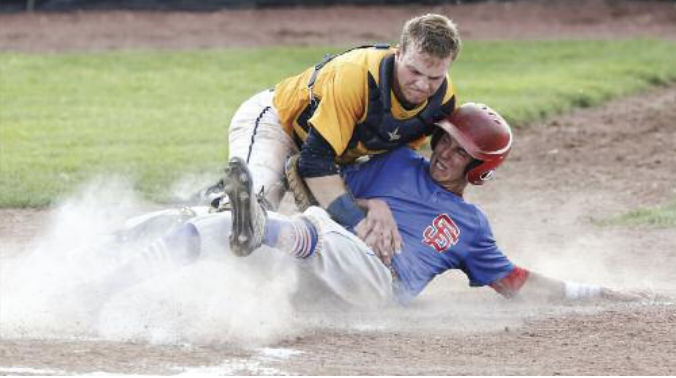

Assuredly, runners on third base will pressure catchers to execute blocking and receiving fundamentals as perfectly as possible. Runners need to interpret in less than a 0.46 of a second [1] the type of pitch, [2] the distance the ball hits the dirt in front of the plate, and [3] if ball is not cleanly blocked or caught, the break and speed of the pitcher in covering the plate. At the peak of the secondary lead, a runner at third base must determine if the pitcher can be beat them

in a race to home plate.

Conclusions

Failure or misreads are bound to occur in ball-in-the-dirt reads. Remedies and improvements are not invented until we experience failures. The sooner a player can learn the aforementioned techniques, it’s only a matter of time before they will become an expert in executing ball-in-the-dirt steals.